The business of unsold inventory can be confusing enough. But add to that the variety of terms and definitions that organizations use, and you’ve got a recipe for miscommunication. Knowing how to define your terms – and, more importantly, how to manage those different categories – is essential for effective management and collaboration between demand planners, inventory control personnel and sales reps.

Back in 2017, we talked about some of the lingo of food inventory. But there are still so many more hard-to-define terms used in the industry that we thought it made sense to expand on that a little bit.

Defining our terms

Slow-moving inventory

Slow-moving is a classification for inventory whereby the current cases on hand exceed projected sales, and therefore are unlikely to be sold based on forecasts prior to the product’s expiration date. To use a simple example, if a manufacturer produced 1,000 cases of a product that expire in a year, and they’ve only sold 50 cases in the first 3 months following production, then chances are they’re going to run into a problem. Slow-moving inventory, also known as excess product, can occur for any number of reasons, but it’s usually a result of inaccurate demand planning models, leading to overproduction.

Many companies will set internal protocols for managing slow-moving inventory. In cases where slow-moving inventory has a lot of shelf life remaining, sales reps will pursue promotions with retailers in an effort to increase demand for it. In other cases, they might start discounting or donating as soon as they realize that it won’t sell.

Avoiding slow-moving inventory is easier said than done, but focusing on market dynamics and customer demand is the best way to make progress. Consistent communication and collaboration between supply chain and sales can help get ahead of problems that emerge from slow-moving inventory.

Obsolete goods

Obsolete goods are products that have been discontinued, have undergone packaging changes, or are out of season. Seasonal items are some of the most common examples. This could be anything from time-based branding (such as calendars with literal dates on them or products associated with new movie releases), to holiday-themed candy, snacks or beverages. For example, Halloween candy loses its shelf presence by November 1, at which point it becomes obsolete (despite it being far from expiration).

Similarly, when a company rebrands a product or makes a design change, many retailers are hesitant to sell (or even restricted from selling) the previous packaging, rendering it obsolete. This is common as manufacturers move toward eco-friendly packaging and experiment with different packaging sizes. Packaging changes can be great for sales — Coca-Cola saw a 10% boost when they introduced the Fridge Pack in 2002 — but can also leave a lot of obsolete inventory.

SKU rationalization is also a complicated process, resulting in winding down SKUs based on either retailer appetite (or lack thereof) or a manufacturer’s desire to concentrate production lines and marketing dollars towards fewer, larger-hitting products. When items are discontinued or SKUs are combined, the discontinued items will often need to go through a discount sales program.

Obsolete goods happen to everyone, but the important thing is knowing how to get ahead of it, manage it effectively and sell it into the right channels.

Short-dated inventory

Distressed inventory is any unsold product that is short-dated. Short-dated, however, means different things depending on where you are in the supply chain. For a consumer, this refers to a food product’s printed expiration date. Retailers, however, want to ensure that inventory coming into their stores has a certain number of days, weeks, months, or even years of shelf life remaining so that end consumers don't have to worry about their grocery products approaching an expiration date. This minimum required days of shelf life remaining is often referred to as a “customer guarantee date”, or a commitment by a manufacturer not to ship products to retailers that don’t meet these shelf life expectations.

Importantly, different retailers have different requirements when it comes to shelf life remaining, and inventory that’s past this customer guarantee date is often still far from its expiration date. Take a can of soup: many retailers require it to have 180 days of shelf life remaining prior to it arriving at a store. Regardless, inventory gets classified as distressed in large part because the number of channels into which it can be sold starts to shrink.

Distressed inventory is common in CPG, in part because CPG manufacturers hold about 50% of all inventory. But it’s especially prevalent in the food, beverage and grocery industries due to perishability. While clothing might go out of season or out of style, it doesn’t often have hard cutoff dates. Plus, many clothing retailers have in-house solutions for distressed inventory: the clearance rack. Food manufacturers don’t typically have that option. Instead, they need to establish more diversified relationships with retailers who have flexibility to take on shorter-dated product in exchange for discounted prices, and ultimately pass those savings onto consumers.

The lines can be blurry

As you can probably tell, these three categories aren’t totally cut and dry. There can certainly be overlap, especially in certain industries.

Take Christmas chocolates, for example. If a manufacturer is sitting on excess product on December 20th, how should they qualify that inventory? Chances are it was slow-moving up until that point, and in five days it’s going to be obsolete, unless the product has enough shelf life for it to make it to next Christmas (unlikely). In this case, if a manufacturer keeps holding onto it, its customer guarantee date will come and go, thus pushing it into true short-dated territory.

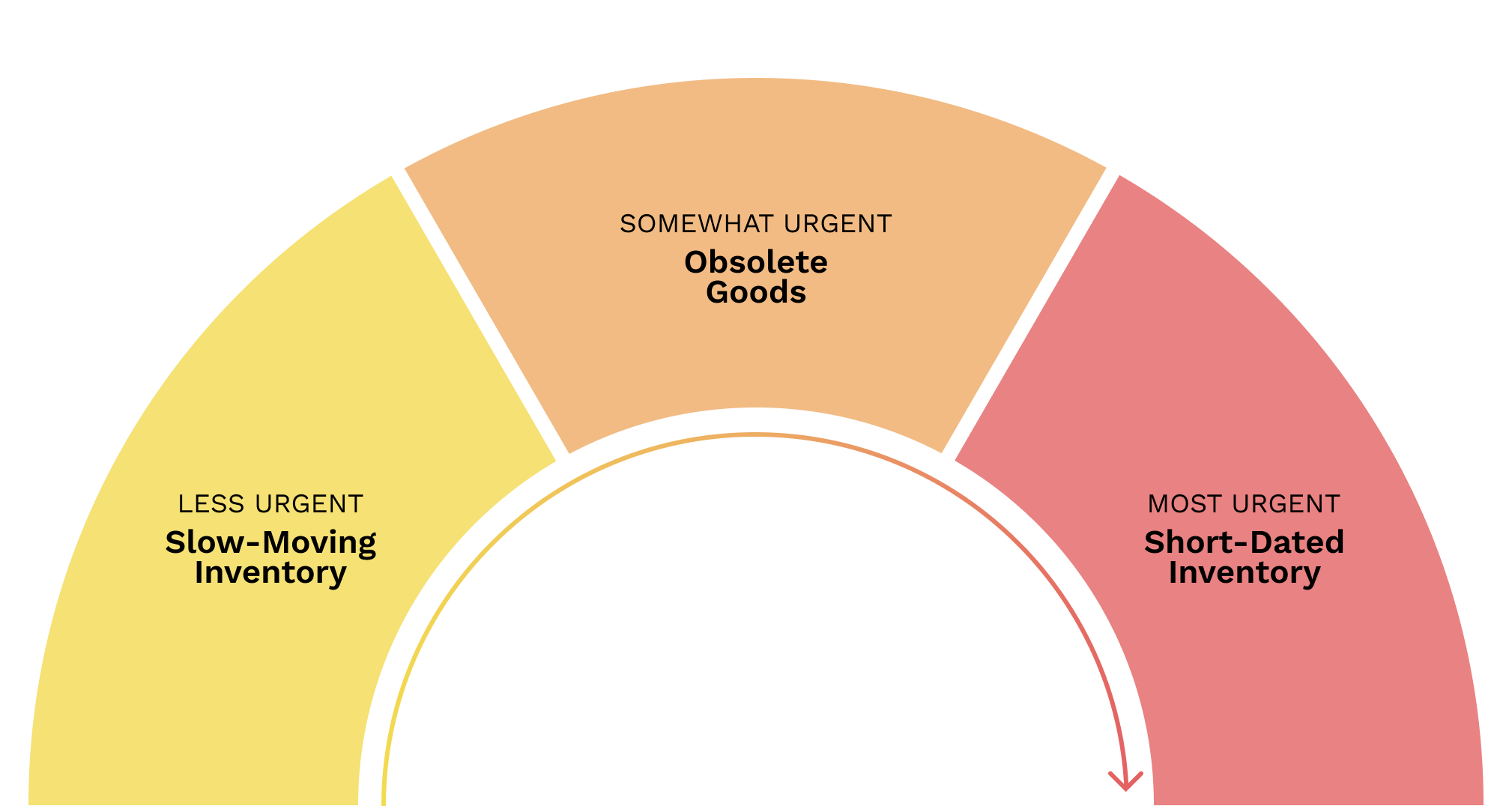

Trying to figure out which single category an item falls into is less important than recognizing that all three categories exist, and that they require different levels of urgency.

- Most urgent: short-dated inventory. If it doesn’t sell before its customer guarantee date, its sales channels narrow significantly. And if it doesn’t sell before its expiration date, it will likely either go to a composting facility or landfill. It’s important to look at all available sales channels to make sure that this perfectly good product gets into the hands of consumers.

- Somewhat urgent: obsolete goods. Obsolete goods are unlikely to sell through primary channels, and the longer they sit, the less valuable they become. For the sake of cost recovery, you’ll want to move these to secondary channels sooner rather than later.

- Less urgent: slow-moving inventory. If your inventory exceeds projected demand, you’re going to be stuck with product in the end. From there, you’ll need to look for other avenues to sell into to free up space in your facilities. But if it doesn’t have an impending expiration date, consider discounting sales to your primary buyers or offering other incentives.

If an item falls into multiple categories, default to the most urgent classification. That way you can act with the appropriate speed and minimize loss.

Facing the challenge

All three of these categories can put strain on a company. The last thing you want is for good inventory to go unsold and end up recycled, composted, or, worst of all, dumped in a landfill.

By recognizing how quickly something needs to be moved, you can identify secondary channels and recover value instead of generating loss. Spoiler Alert is the leading platform dedicated to selling unsold perishable inventory into discount channels. With a digital platform, you can accelerate sales, build relationships with your buyers and recover more value for your company.

To learn more about the impact Spoiler Alert could have for your organization, download our case study with KeHE.

.png?width=250&name=SpoilerAlert_WhiteLogo_LeftStacked%20(7).png)