Banana peels. Oversized apples. Mislabeled packaged goods.

In different circles, these products might be considered ‘food waste’, yet in others, they might represent a meal or an input for value-added processing. Awareness of the food waste problem has increased tremendously, catalyzing action from the private, public, and civil sectors to develop solutions to an issue that costs the U.S. $218 billion every year. But even among the experts and practitioners leading the charge, you may find mixed definitions of what constitutes ‘food waste’.

Background on the Food Loss and Waste Standard

That is why in 2013, a multi-stakeholder partnership named the Food Loss & Waste Protocol set out to develop an internationally-recognized standard that outlines requirements and guidance for measuring and reporting on the weight of food and/or associated inedible parts that are removed from the supply chain, otherwise known as ‘food loss and waste’ (FLW).

What this group produced and launched in 2016 is known as the Food Loss and Waste Accounting and Reporting Standard (FLW Standard). Led by the World Resources Institute (WRI), the partnership includes representatives from the Consumer Goods Forum (CGF) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), with review and feedback provided by more than 200 additional stakeholders from business, government, civil society, and academia.

Major Components & Definitions

The true purpose of the FLW Standard is “to facilitate the quantification of FLW... and encourage consistency and transparency of the reported data.” By using the FLW Standard, an entity (whether it be a business, institution, or municipality) is able to create an inventory to identify how much FLW is generated and where it is going, then subsequently compare performance among peers that are also using the tool.

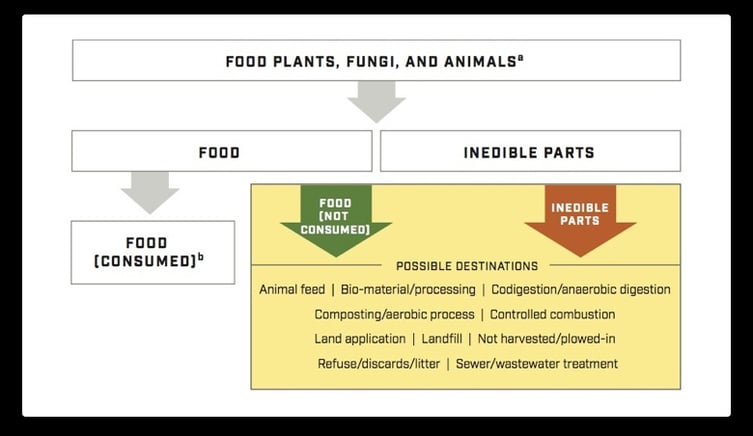

Underlying motivations for quantification will impact how an entity defines what makes up FLW. The FLW Standard is designed to accommodate this by allowing for flexible definitions of FLW, defining possible components in terms of ‘destination’ (where material removed from the supply chain is destined, see examples in diagram below) and ‘material type’ (either Food or Inedible Parts):

- Food: Any substance (processed, semi-processed, or raw) that is intended for human consumption, which also includes drinks and spoiled food.

- Inedible Parts: Components associated with a food that, in a particular food supply chain, are not intended to be consumed by humans (e.g., rinds and bones).

Figure 1. Material Types and Possible Destinations Under the FLW Standard. Image from the FLW Standard.

The FLW Standard also allows an entity to choose from a suite of quantification methods, ranging from waste composition analysis to proxy data. Entities should choose a quantification method that provides the level of accuracy to meet their needs.

Reporting Requirements

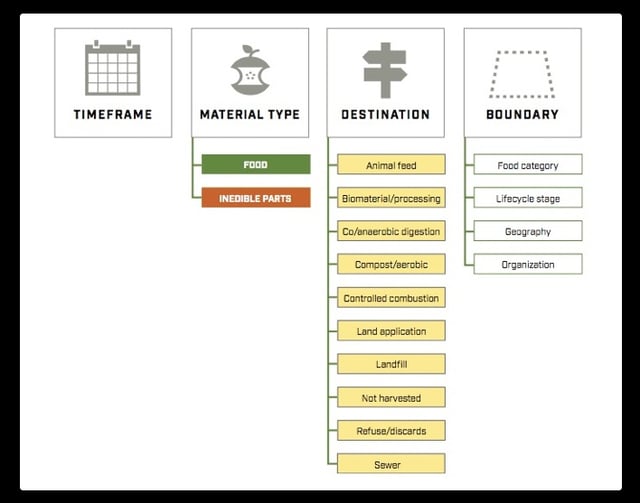

Regardless of motivations and definitions, the FLW Standard requires an entity to define the scope for their FLW inventory by way of four components:

- Timeframe: Period of time for which inventory results are being reported.

- Material type: The materials that are included in the inventory (food only, inedible parts only, or both)

- Destination: Where FLW goes when removed from the supply chain

- Boundary: The food category, lifecycle stage, geography, and organization

Figure 2. Scope of an FLW Inventory. Image from the FLW Standard.

When ready to actually carry out an inventory, the FLW Standard provides clear instructions on how to define scope, as well as a step-by-step guide for implementation.

Why Measure and Report?

Any entity, regardless of scale, economic sector, or geography, can utilize the FLW Standard to develop an inventory for FLW. As awareness of the food waste issue increases, there is mounting pressure, both internally and externally, on companies to report these volumes. Reasons to quantify and report out FLW may include:

- Internal Corporate Commitments: Major companies, including the 2030 Food Loss and Waste Champions and Champions 12.3, have committed to halving FLW by 2030. To gauge progress, measurement is required.

- Shareholder Requests: FLW is a major financial burden, and investors may soon start to take notice. Trillium Asset Management has started directly engaging companies like Whole Foods and Target to report on FLW generation and actions to mitigate the issue.

- Customer Engagement: The topic of ‘food waste’ has gained considerable traction over the last five years, and it is likely that more customers (both businesses and consumers alike) will begin to demand action from suppliers and retailers. Getting ahead of the game and starting to quantify FLW now can pay off in the future.

For examples of companies that have utilized the FLW Standard to quantify FLW, check out these case studies.

What’s Next?

It will be exciting to follow the evolution of the FLW Standard as more entities sign on to utilizing the tool. The first iteration of the GHG Protocol, the internationally recognized standard for measuring and reporting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, was introduced in 2001. By 2014, 86% of Fortune 500 companies reporting environmental impacts through CDP utilized the GHG Protocol. In addition, the GHG Protocol formalized the practice of measuring and reporting GHG emissions, and now it is hard to identify companies that don’t do some sort of measurement.

There is a reason for the saying ‘What gets measured, gets managed.” If entities truly want to get in the game when it comes to food waste measurement, the FLW Standard is great place to start.

.png?width=250&name=SpoilerAlert_WhiteLogo_LeftStacked%20(7).png)